Findings of this study suggest that reducing ideas of vulnerability and resilience into ‘scalar’ parameters can achieve limited success in mitigating newer forms of risks induced by climate change.

Authors

Aditya Ghosh, University of Leicester, UK; Associate Professor, Jindal School of Art and Architecture, Jindal Global University, Sonipat, Haryana, India.

Amrita Sen, Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur, India.

Marina Frietsch, M.Sc. Sustainability Science, Leuphana University, Lüneburg; Germany.

Summary

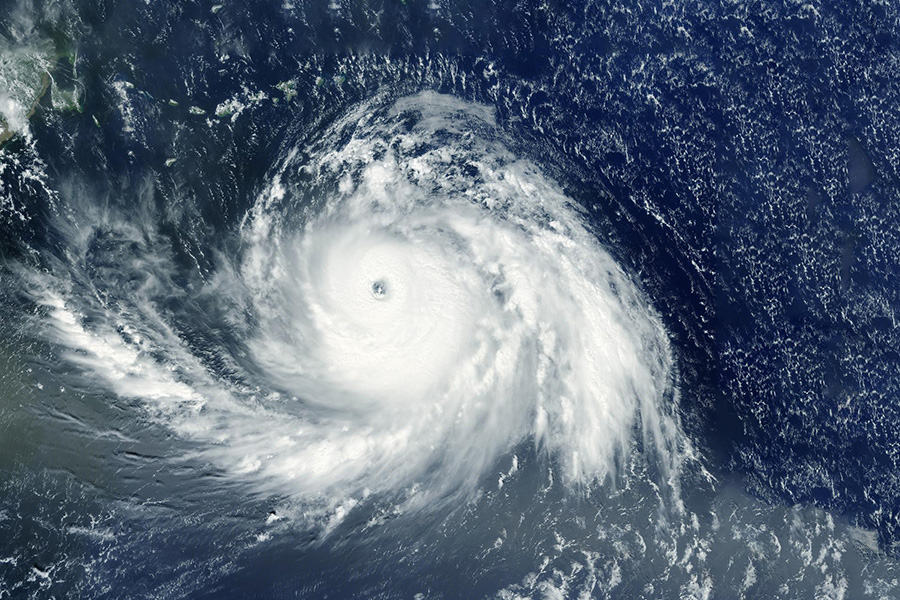

Significant advancements in climate and meteorological sciences, communication technologies and geo-engineering in the past decade have had limited success in mitigating losses and damages from disasters originating in the environmental domain. At an average of US$250 billion–US$300 billion a year, total losses and damages from disaster between 1998 and 2017 reached $2.9 trillion, 90% of which were climate-related disasters. This is a rise of 151% when compared with losses and damages of $1.3 trillion between 1978 and 1998 [147](UNDRR 2018). US recorded maximum losses followed by China, Japan and India. This, however, constitutes reported and documented losses only, no loss data was available for nearly 87% of disasters in low-income countries, even high-income countries reported losses from 53% of disasters (ibid).

Also, the spatial distribution of losses was extremely uneven – an average of 130 people died per million living in disaster-affected areas in low- and middle-income nations compared to just 18 people in high-income countries since 2000, demonstrating that while absolute economic losses might be concentrated in high-income countries because of the high asset values, human costs of disasters are borne overwhelmingly by the low and lower-middle income countries.

Also, relative losses are not reflected in this data (as percentage of household income, for example), which are often significantly higher in lower- and middle-income countries compared to high income ones despite the latter suffering greater financial losses because of high-value infrastructure.

Published in: International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction

To read the full article, please click here.