Maaz Bin Bilal’s translation and his extensive introductory commentary on Chirag-e-Dair, or Temple Lamp is important for the way it liberates both Banaras and Ghalib from the clutches of discursive constructs that have held them captive in colonial and postcolonial politics.

Author

Srimati Ghosal, Assistant Professor, Jindal Global Law School, O.P. Jindal Global University, Sonipat, Haryana, India.

Summary

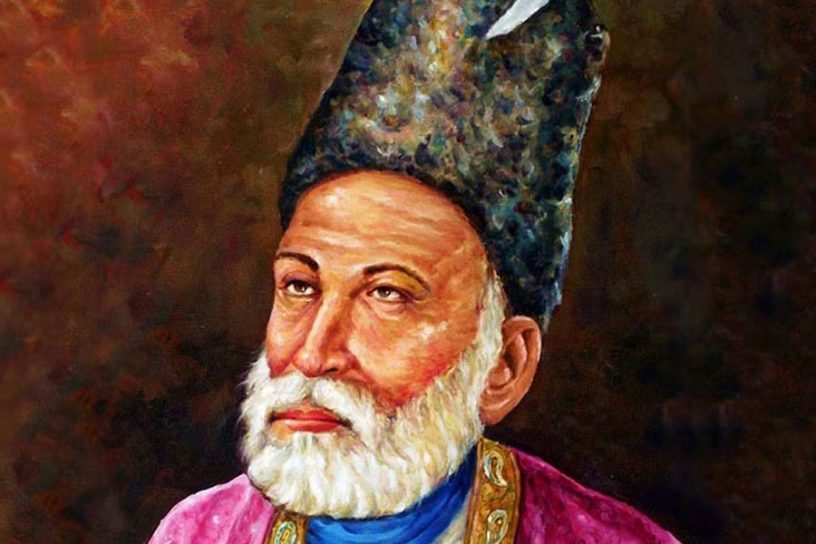

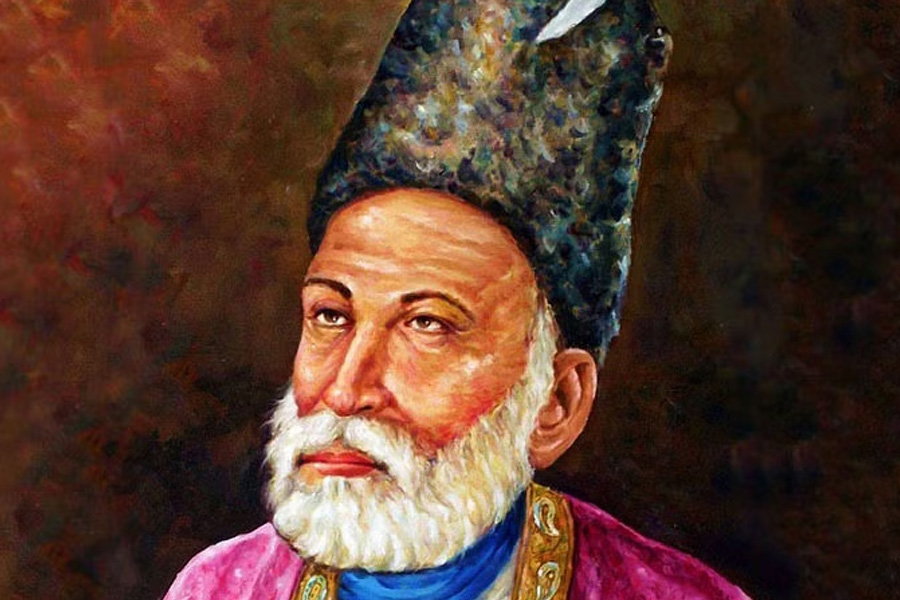

Mirza Asadullah Beg Khan, popularly known by his pen name Ghalib, lived in Delhi during the decline and demise of the Mughal Empire among the Persian-speaking ruling elite of the city even though his personal life was riddled with financial difficulties and debt. Ghalib wrote in both Persian and Urdu, though his popularity today rests more on his Urdu oeuvre than the much larger body of work he composed in Persian. Having witnessed and lived through the Revolt of 1857 that saw the end of the Mughal Empire, Ghalib mourned extensively for his beloved Delhi fallen to foreign rule.

A largely nonpracticing Muslim, he has been seen as one capable of questioning his faith through much of his Urdu oeuvre. This has often resulted in his neat assimilation into the narrative of secular nationalism born during the anti-imperialist struggle and arduously disseminated by the governments of independent India in the second half of the twentieth century. For example, a TV series on Ghalib produced by Doordarshan, the only state-run television channel in pre-liberalization India, often has him express great pain at “division among Shias and Sunnis, Hindus and Muslims, Delhi and Agra”. Despite being born to the ruling elite and having lived through a revolt that changed the fate of the subcontinent, great financial hardships, and professional failures and some brilliant success, it is ironic that his after-life went on to assume even more interesting political and cultural significance than his own.

Maaz Bin Bilal, a thorough and recognized scholar, accomplished translator, and gifted poet, seeks to deconstruct this Ghalib that South Asians across the globe have grown up with and re-introduce them to the poet. This is his third book after authoring Ghazalnama: Poems from Delhi, Belfast and Urdu and a translation of Fikr Tausvi’s Urdu diary into English, The Sixth River: A Journal from the Partition of India. He has been variedly trained under various prestigious fellowships including the Charles Wallace India Trust Fellowship in Translation and Writing (Nov. 2018–Feb 2019) and brings his clear understanding of the language and poetics of Persianate poetry to this work, often meticulously describing poetic form- meters, construction of distiches, refrain and rhyme- and context for the uninitiated reader.

Published in: South Asia Monitor

To read the full article, please click here.